New York Times headline from November 10, 1909.

In November of 1909, an amateur hypnotist named William Davenport attempted to extend the powers of his art to an entirely new level. He tried to wake the dead.

The scene took place in a Somerville, New Jersey morgue, where Davenport leaned over the body of Robert Simpson, a 35-year-old piano mover and former Newark street car conductor. The hypnotist pressed his ear to the dead man’s chest listening for a trace of a heartbeat, then touched Simpson’s cheeks and whispered into his ear, “Bob, your heart action—attend. Listen, Bob, your heart action is strong. Bob, your heart begins to beat.”

No luck. So Davenport tried shouting.

“Bob, do you hear me?”

Simpson heard nothing. Still, the hypnotist persisted, whispering again, “Bob, your heart is starting.”

Davenport’s efforts were at the behest of another hypnotist, Arthur Everton, who would’ve made his own attempts to revive Simpson had he not been sitting in a prison cell.

Everton had held a performance the evening before at the Somerville Opera House and put Simpson under a trance on stage. As the stunt was concluding, he died right in front of the audience.

Simpson was working with Everton as a “leader,” meaning that the showman would call for volunteers to go under his spell, and the “leader” would be the first to raise his hand. The theory being that after a show of success, others would happily elect to be hypnotized as well.

But not on this night. According to a November 10, 1909 New York Times article, here’s what took place on stage:

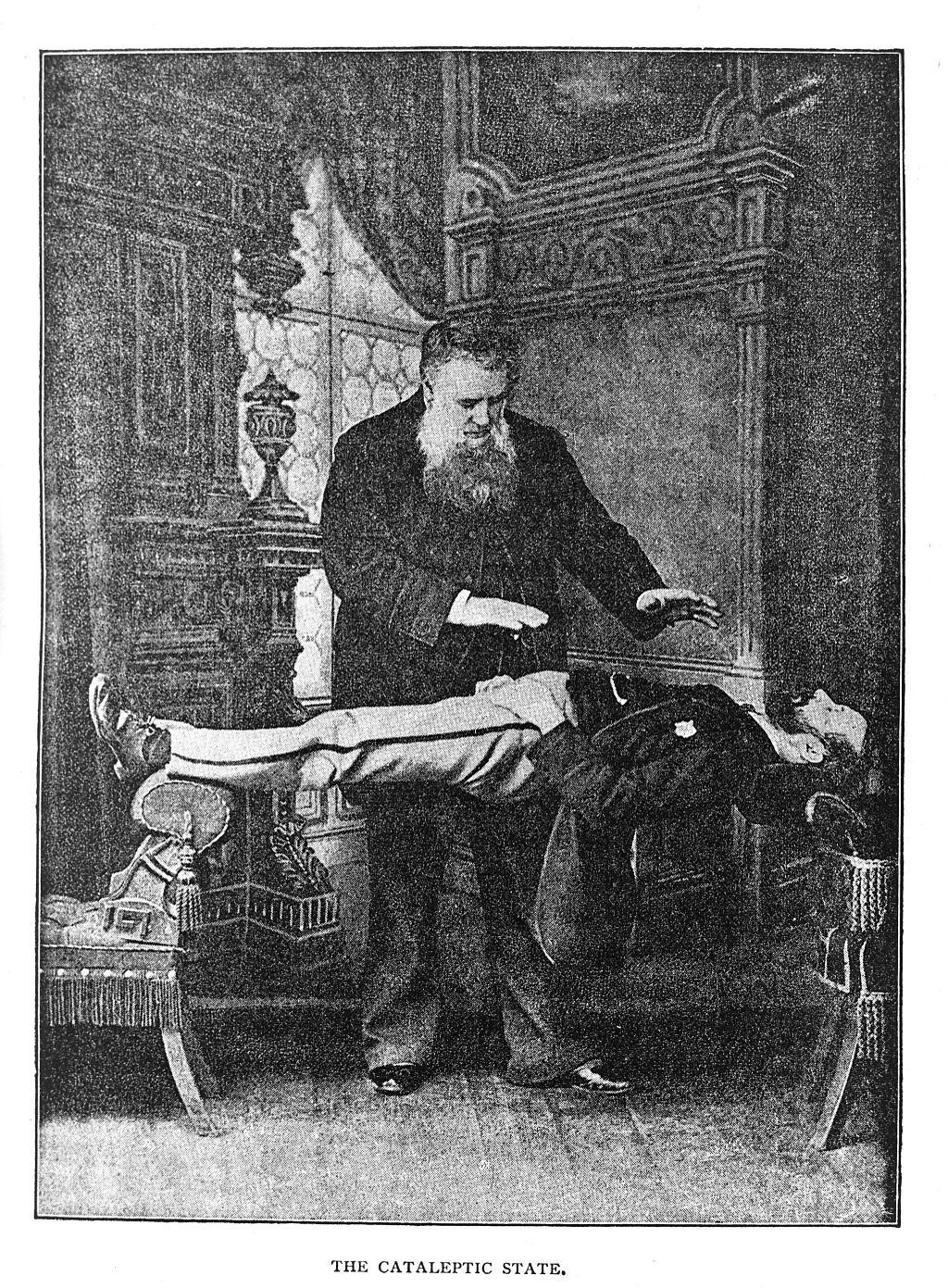

He made a few passes, told Simpson to be rigid, and he was. Everton then had attendants lay the body on two chairs, the head resting on one and the feet on the other, and stepped up on the subject’s stomach and then down again. Two attendants, acting under his orders, lifted Simpson to a standing posture, and Everton, clapping his hands, cried out ‘Relax!’

Simpson’s body softened so suddenly that it slipped out of the hands of the attendants to the floor, his head striking one of the chairs as he slid down.”

Doctors at the theater rushed to help, but it was too late. They pronounced him dead.

Charged with manslaughter, Everton was desperate to avoid making his time in jail permanent. He believed Simpson might still be in a cataleptic state and just needed to be awakened. He pleaded with authorities to allow Davenport, a friend, to prove him right. A fellow authority on hypnotism, and Professor Emeritus at Columbia University, Dr. John Duncan Quackenbos, agreed that suspended animation was a possibility.

After Davenport’s failed resuscitation attempts, an autopsy showed Simpson died from a ruptured aorta.

According to an article from the Kentucky New Era, “Death was practically instantaneous and evidently occurred just as Simpson was coming out of the trance. Whether the strain he was put under when Everton stood on the body during its rigidity caused the rupture cannot be ascertained.”

Doctors believed natural causes were mostly to be blamed, and that Simpson had been suffering from an earlier condition. The timing of his death was likely an unfortunate coincidence.

He was eventually released on bail and shortly after, in December, a grand jury decided not to prosecute him.

Eleven years later, Everton had another brush with the law when $6,000 worth of liquor was seized from his apartment in a prohibition raid. He claimed that he could’ve used his hypnotic powers to stop them, but chose not to. When asked why, he told the New York Times, “I wouldn’t do that. I am a law-abiding citizen.”

One experience in prison was more than enough.