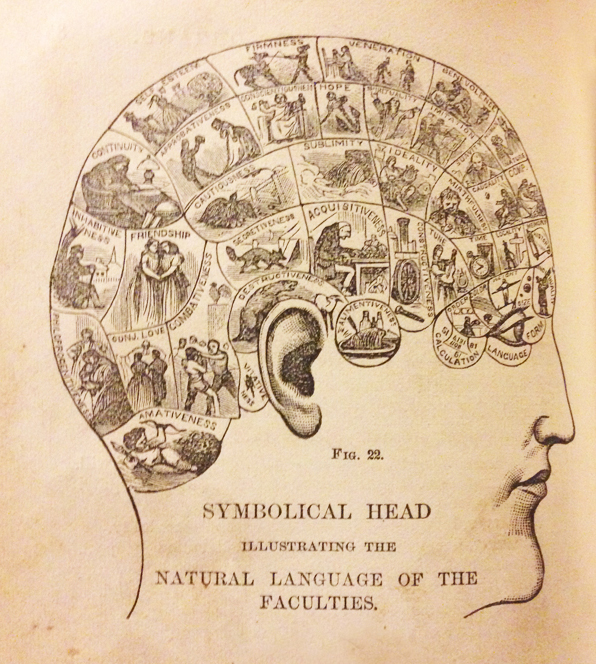

The science of phrenology was developed in the late 18th century as a way to explain the intellectual and moral character of a man through the special elevations and depressions within the cranium, formed by the physiology of the brain. The brain is the organ of the mind, and each faculty of the mind has its own special organ in the brain. These faculties, phrenologists claimed, could be improved by cultivation and deteriorated through neglect.

In reading people’s heads, phrenologists scored individual characteristics regarding Amativeness, Inhabitiveness, Adhesiveness, Philoprogenitiveness, Benevolence, Veneration, Mirthfulness, Ideality, Conscientiousness, Alimentiveness and other excessively long words describing simple traits.

Misguided as this science was, it did provide some wondrous illustrations mapping out these regions of the head, as pictured.

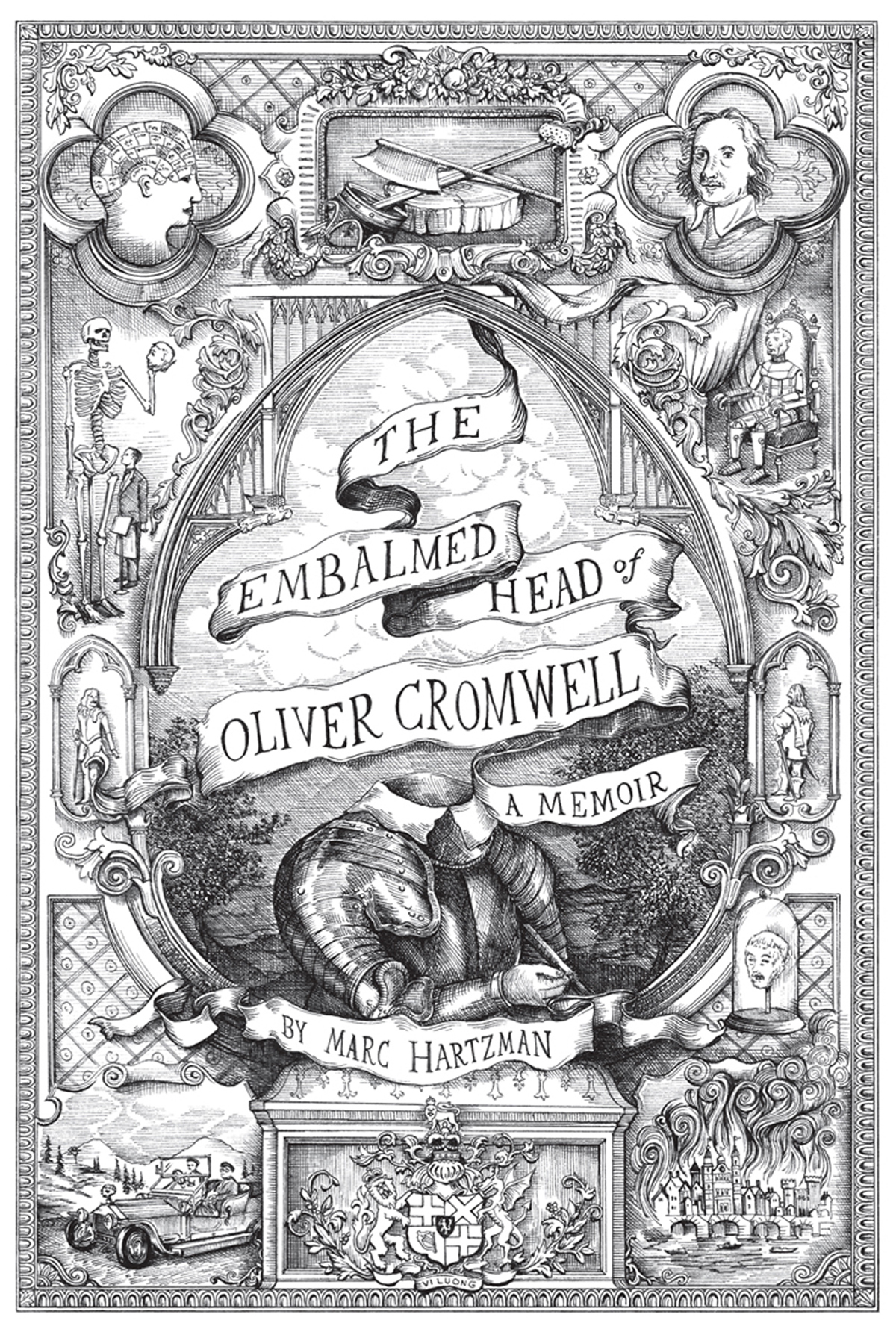

All of this, of course, was practiced long after Oliver Cromwell, the Lord Protector of England, Ireland and Scotland died. (The Protectorship was a title he accepted shortly after Charles I was beheaded on January 30, 1649.) But luckily for phrenologists, Cromwell was embalmed and buried, exhumed, and then beheaded. After twenty-five years on a spike atop Westminster Hall, the head fell off in a storm and was picked up and taken home by a sentry.

The embalmed head passed through numerous hands before being reburied in 1960 at Sidney Sussex College in Cambridge (Cromwell’s alma mater).

Read more about his journey in my book, The Embalmed Head of Oliver Cromwell: A Memoir. In it, I have his head visit a phrenologist, based off a real examination by C. Donovan, as reported in The Phrenological Journal and Magazine of Moral Science from 1844.

Below are a few excerpts from Donovan’s reading, filled with phrenological babble:

The region of the religious feelings is quite as fully developed as a correct knowledge of his character, in a religious point of view, would lead us to expect. The region is globular, though not marked by any conspicuous prominences; and the observation of a connoisseur could not fail to fix itself thereon. Nevertheless, in my judgment, no one would be justified in saying that this is the head of a fanatic. For there is a perspicacity, a clearness of observation, evinced by the well-formed perceptive region, and a strength of reflection in the upper part of the forehead, under the control and guidance of which it is highly improbable that an educated man, not placed under influences acting almost exclusively on the religious feelings, could pass into a state of general mental action to which the term fanaticism might be correctly applied.”

As a knowledge of his character would lead us to expect, we find in Cromwell’s skull Secretiveness and Cautiousness emphatically indicated. In the head of Cromwell, the phrenologist, whatever estimate he might have been led to form of the character of the man, in its totality, would expect to find a very full development of Destructiveness, Secretiveness, Caution, and Wonder (or Belief), as well as of the organs of the intellect. Such are found in the skull we are examining. The region of Wonder is absolutely, as well as relatively, very large. I have seen one or two heads with a more prominent development of this region, but these were monstrosities; and I believe that a larger development has never been seen in any well-proportioned head.”

The skull, though well developed, is not of a graceful type, nor has it that gradual sweep of elevation, from the seat of Individuality to that of Firmness, which is presented by heads of the highest class. Vigour and perspicacity of reflective intellect, strength of will, depth of religious feeling, are all strongly conveyed; but we do not find a sufficient development of that organ, which, controlling in some measure the impulsive action of all the others, gives time for the mediation of accurate observation, calm reflection, and just judgment, before the consent of the mind is yielded to the fearful execution of the worst that man can inflict upon his brother man. And, accordingly, actuated by the sanguinary and vindictive excitements of his dreadful task, that, to quote Shakespeare, ‘Consideration like an angel came, and whipped th’ offending Adam out of him.’ If not deliberately cruel, Cromwell was, at least, indifferent to the shedding of human blood; and of this fact, his conduct at Dunbar, at Cork, and at Wexford, where it glared out with hideous certainty, will not permit us to doubt.”

When the head now under inspection was severed from the trunk, at Tyburn, it was so mutilated by an ill-directed blow of the axe, that there is scarcely a possibility of estimating, with accuracy, the development of the region of the cerebellum; it seems, however, from the volume of the adjacent parts, as well as from other indications, to have been large.

Conscientiousness I find large, much larger than I had expected; a fact which a clerical friend of mine, to whom it was mentioned, strenuously urged on me as evidence unfavorable to the presumption of the genuineness of the head. But I persuade myself that a more candid and a closer examination of Cromwell’s character, must lead to a different conclusion. We must bear in mind, that more than two hundred years of knowledge of civilization, and of social advancement, have shed their blessed influences upon society since that character was formed; and that even his darker vices, his ruthless ferocity, for example, and his dissimulation, do not justify the inference that the man was as wicked as we of this age must become, before we could do the like. To a phrenological eye, the hollow dome of bone before me tells, in language as convincing as it is eloquent, that the kingdom of its occupant’s soul was divided against itself.”

After having stated me entire and unhesitating conviction that the head of which I am now writing is indeed the skull of Cromwell, I shall perhaps raise a smile of incredulity when repeating, that the region of Conscientiousness is well developed, the arch from Firmness to Caution being fully and harmoniously formed. But the scoffers will only be such as have yet to learn the true theory of the human mind.”

Cromwell’s embalmed head enjoyed many other adventures, all recounted in the head’s memoir, and summarized in the song by Stephie Coplan below.