Wars. Famine. Disease. If there was one thing medieval Europe was never in short supply of, it was funerals. And as with all upward trends throughout history, entrepreneurship abounds.

For god-fearing folk during the religious climate of the Middle Ages, the only thing worse than death was Purgatory, and The Church held a monopoly on absolution. While nobility could pay local bishops to absolve a loved one’s sins upon death, commoners could not afford such luxuries. However, there was another, albeit, macabre option.

Ars moriendi (The Art of Dying), circa 1460 Netherlands. Artist unknown. Woodblock.

Unaffiliated with any church or parish, sin-eaters roamed the feudalistic countrysides of England, Scotland, and Wales, and for a mere six-pence and a meal, offered a quick ascension to Heaven for the recently departed.

As one can imagine though, with a ritual as morbid as the profession’s name implies, the ritual needed to be provided with the utmost discretion.

Once the service of a sin-eater had been discreetly procured, the deceased would be bathed for burial by loved ones. Family members would then lay out the corpse beside a flagon of ale and place a loaf of bread on his or her chest.

Believing that the bread would absorb the sins, the sin-eater would quietly enter the home in the dead of night, recite an incantation and devour the meal. Upon ensuring the deceased’s entry into the kingdom of Heaven, the he would then slip back out into the darkness and the obscurity of the countryside.

Psalter (the ‘de Lisle Psalter’), circa 1310 – 1320. Artist unknown. Illustrated manuscript.

Why a process worthy of a horror movie? Sin-eaters were reviled throughout history despite providing a necessary function for the believers. In addition to only the most wretched and destitute finding such a profession worthwhile, it was believed that these eternally damned individuals grew more depraved with every sin they consumed.

Though by the 1800s the rituals had evolved from its macabre past into that of a more symbolic meal, sin-eating was still reviled by a pious, “civilized” society.

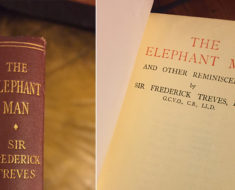

In his book Funeral Customs, Bertram S. Puckle published the writings of a Professor Evans of the Presbyterian College, Carmarthen, who in 1825 described a known sin-eater that he had encountered:

Abhorred by the superstitious villagers as a thing unclean, the sin-eater cut himself off from all social intercourse with his fellow creatures by reason of the life he had chosen; he lived as a rule in a remote place by himself, and those who chanced to meet him avoided him as they would a leper. This unfortunate was held to be the associate of evil spirits, and given to witchcraft, incantations and unholy practices; only when a death took place did they seek him out, and when his purpose was accomplished they burned the wooden bowl and platter from which he had eaten the food handed across, or placed on the corpse for his consumption.

The last recorded sin-eater, Richard Munslow, died in 1906. It is said that he had taken up the trade out of grief, following the devastating loss of his four children to whooping cough.

Despite the fact that sin-eaters were shunned by established religious organizations, Richard was buried in the graveyard of Ratlinghope Church in Shropshire, England and his grave was restored and commemorated in 2010.

While we’ll never know if his soul reached its heavenly destination, in an interview with the BBC, the vicar of Ratlinghope summed up the occasion quite nicely:

“This grave at Ratlinghope is now in an excellent state of repair but I have no desire to reinstate the ritual that went with it.”