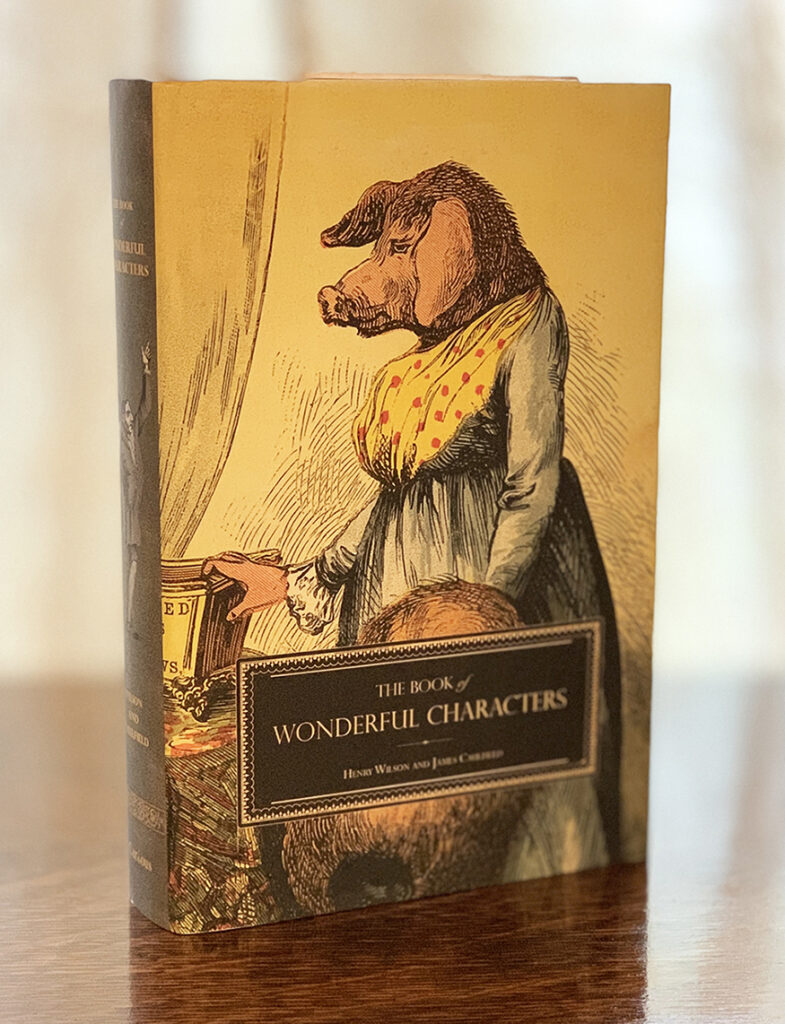

In the early years of the 19th century, an armless woman called Miss Biffin was seen annually at England’s Bartholomew Fair and other events. “She worked with her toes neatly at her needle, and was very ingenious in designing and cutting out patterns in paper,” describe Henry Wilson and James Caulfield in The Book of Wonderful Characters, adding that she “was a person really capable of showing talent as a miniature painter, without hands or arms.”

Miss Biffin is just one of more than 75 wonderful characters featured within this re-publication of the 1869 original edition. Once famous across their respective countries, or even just their local towns, these remarkable people are now brought back to life to have their stories shared again. And to stir the wonder, imagination, and fascination of the modern reader.

Three more examples are below: a horned man, an armless wonder, and a water spouter.

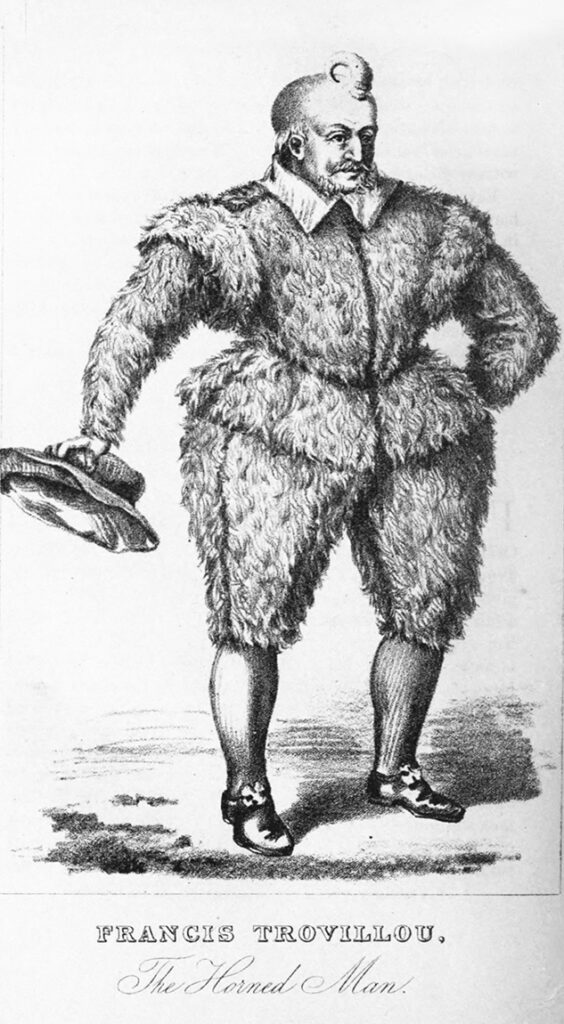

Francis Trovillou, The Horned Man.

In the year 1598 a horned man was exhibited for a show, at Paris, two months successively, and from thence carried to Orleans, where he died soon after. His name was Francis Trovillou, of whom Fabritius, in his Chirurgical Observations, gives the following description: — “He was of a middle stature, a full body, bald, except in the hinder part of the head, which had a few hairs upon it; his temper was morose, and his demeanour altogether rustic. He was born in a little village called Mezières, and bred up in the woods amongst the charcoal men. About the seventh year of his age he began to have a swelling in his forehead, so that in the course of about ten years he had a horn there as big as a man’s finger-end, which afterwards did admit of that growth and increase, that when he came to be thirty-five years old this horn had both the bigness and resemblance of a ram’s horn. It grew upon the midst of his forehead, and then bended backward as far as the coronal suture, where the other end of it did sometimes so stick in the skin that, to avoid much pain, he was constrained to cut off some part of the end of it. Whether this horn had its roots in the skin or forehead, I know not; but probably, being of that weight and bigness, it grew from the skull itself. Nor am I certain whether this man had any of those teeth which we call grinders. It was during this man’s public exposure in Paris, (saith Urstitious), in 1598, that I, in company with Dr. Jacobus Faeschius, the public Professor of Basil, and Mr. Joannes Eckenstenius, did see and handle this horn.”

Miss Hawtin, Born without Arms.

MISS HAWTIN was a native of Coventry, born without arms, and remarkable for the dexterity with which her feet performed all the offices of hands. With her toes she would cut out watch-papers, with such ingenuity and despatch as to astonish every beholder; and numbers of these papers were kept as great curiosities by many who visited her. She could likewise use her needle and her pen with great facility. These extraordinary talents she exhibited to the great gratification of the public, in almost every town of England, till shortly before her death.

Floram Marchand, The Great Water-Spouter.

IN the summer of 1650, a Frenchman named Floram Marchand was brought over from Tours to London, who professed to be able to “turn water into wine, and at his vomit render not only the tincture, but the strength and smell of several wines, and several waters.” He learnt the rudiments of this art from Bloise, an Italian, who not long before was questioned by Cardinal Mazarin, who threatened him with all the miseries that a tedious imprisonment could bring upon him, unless he would discover to him by what art he did it. Bloise, startled at the sentence, and fearing the event, made a full confession on these terms, that the Cardinal would communicate it to no one else.

From this Bloise, Marchand received all his instruction; and finding his teacher the more sought after in France, he came by the advice of two English friends to England, where the trick was new. Here — the cause of it being utterly unknown — he seems for a time to have gulled and astonished the public to no small extent, and to his great profit.

Before long, however, the whole mystery was cleared up by his two friends, who had probably not received the share of the profits to which they thought themselves entitled. Their somewhat circumstantial account runs as follows; —

“To prepare his body for so hardy a task, before he makes his appearance on the stage, he takes a pill about the quantity of a hazel nut, confected with the gall of an heifer, and wheat flour baked. After which he drinks privately in his chamber four or five pints of luke-warm water, to take all the foulness and slime from his stomach, and to avoid that loathsome spectacle which otherwise would make thick the water, and offend the eye of the observer.

“In the first place he presents you with a pail of lukewarm water, and sixteen glasses in a basket, but you are to understand that every morning lie boils two ounces of Brazil thin-sliced in three pints of running water, so long till the whole strength and colour of the Brazil is exhausted: of this he drinks half a pint in his private chamber before he comes on the stage: you are also to understand that he neither eats nor drinks in the morning on those days when he comes on the stage, the cleansing pill and water only excepted; but in the evening will make a very good supper, and eat as much as two or three other men who have not their stomachs so thoroughly purged.

“Before he presents himself to the spectators, he washes all his glasses in the best white-wine vinegar he can procure. Coming on the stage, he always washes his first glass, and rinses it two or three times, to take away the strength of the vinegar, that it may in no wise discolour the complexion of what is represented to be wine.

“At his first entrance, he drinks four and twenty glasses of luke-warm water, the first vomit he makes the water seems to be a full deep claret: you are to observe that his gall-pill in the morning, and so many glasses of luke-warm water afterwards, will force him into a sudden capacity to vomit, which vomit upon so much warm water, is for the most part so violent on him, that he cannot forbear if he would.

“You are again to understand that all that comes from him is red of itself, or has a tincture of it from the first Brazil water; but by degrees, the more water he drinks, as on every new trial he drinks as many glasses of water as his stomach will contain, the water that comes from him will grow paler and paler. Having then made his essay on claret, and proved it to be of the same complexion, he again drinks four or five glasses of the luke-warm water, and brings forth claret and beer at once into two several glasses: now you are to observe that the glass which appears to be claret is rinsed as before, but the beer glass not rinsed at all, but is still moist with the white-wine vinegar, and the first strength of the Brazil water being lost, it makes the water which he vomits up to be of a more pale colour, and much like our English beer.

“He then begins his rouse again, and drinks up fifteen or sixteen glasses of luke-warm water, which the pail will plentifully afford him: he will now bring you up the pale Burgundian wine, which, though more faint of complexion than the claret, he will tell you is the purest wine in Christendom. The strength of the Brazil water, which he took immediately before his appearance on the stage, grows fainter and fainter. This glass, like the first glass in which he brings forth his claret, is washed, the better to represent the colour of the wine therein.

“The next he drinks comes forth sack from him, or according to that complexion. Here he does not wash his glass at all; for the strength of the vinegar must alter what is left of the complexion of the Brazil water, which he took in the morning before he appeared on the stage.

“You are always to remember, that in the interim, he will commonly drink up four or five glasses of the luke-warm water, the better to provoke his stomach to a disgorgement, if the first rouse will not serve turn. He will now (for on every disgorge he will bring you forth a new colour), he will now present you with white wine. Here also he will not wash his glass, which (according to the vinegar in which it was washed) will give it a colour like it. You are to understand, that when he gives you the colour of so many wines, he never washes the glass, but at his first evacuation, the strength of the vinegar being no wise compatible with the colour of the Brazil water.

“Having performed this task, he will then give you a show of rose-water; and this indeed, he does so cunningly, that it is not the show of rose-water, but rose-water itself. If you observe him, you will find that either behind the pail where his luke-warm water is, or behind the basket in which his glasses are, he will have on purpose a glass of rose-water prepared for him. After he has taken it, he will make the spectators believe that he drank nothing but the luke-warm water out of the pail; but he saves the rose-water in the glass, and holding his hand in an indirect way, the people believe, observing the water dropping from his fingers, that it is nothing but the water out of the pail. After this he will drink four or five glasses more out of the pail, and then comes up the rose-water, to the admiration of the beholders. You are to understand, that the heat of his body working with his rose-water gives a full and fragrant smell to all the water that comes from him as if it were the same.

“The spectators, confused at the novelty of the sight, and looking and smelling on the water, immediately he takes the opportunity to convey into his hand another glass; and this is a glass of Angelica water, which stood prepared for him behind the pail or basket, which having drunk off, and it being furthered with four or five glasses of luke-warm water, out comes the evacuation, and brings with it a perfect smell of the Angelica, as it was in the rose-water above specified.

“To conclude all, and to show you what a man of might he is, he has an instrument made of tin, which he puts between his lips and teeth; this instrument has three several pipes, out of which, his arms a-kimbo, and putting forth himself, he will throw forth water from him in three pipes, the distance of four or five yards. This is all clear water, which he does with so much port and such a flowing grace, as if it were his masterpiece.

“He has been invited by divers gentlemen and personages of honour to make the like evacuation in milk, as he made a semblance in wine. You are to understand that then he goes into another room, and drinks two or three pints of milk. On his return, which is always speedy, he goes first to his pail, and afterwards to his vomit. The milk which comes from him looks curdled, and shows like curdled milk and drink. If there be no milk ready to be had, he will excuse himself to his spectators, and make a large promise of what he will perform the next day, at which time being sure to have milk enough to serve his turn, he will perform his promise.

“His milk he always drinks in a withdrawing room, that it may not be discovered, for that would be too apparent, nor has he any other shift to evade the discerning eye of the observers.

“It is also to be considered that he never comes on the stage (as he does sometimes three or four times in a day) but he first drinks the Brazil water, without which he can do nothing at all, for all that comes from him has a tincture of the red, and it only varies and alters according to the abundance of water which he takes, and the strength of the white-wine vinegar, in which all the glasses are washed.”

Want a copy? Check out The Book of Wonderful Characters at Curious Publications.