Hypnotizing people to cluck like chickens can be wonderfully entertaining for audiences, but what happens when the commands given aren’t so harmless?

In September of 1894, a Hungarian hypnotist named Franz Neukomm gave a hypnotic séance at a dinner party and placed the host’s daughter under a trance. He told her she was suffering from consumption. The girl then shrieked and fell to the floor, dead. Luckily for the hypnotist he wasn’t convicted of murder. Neukomm was cleared at his trial since it was believed death could occur at any time—it just happened to be a terrible coincidence.

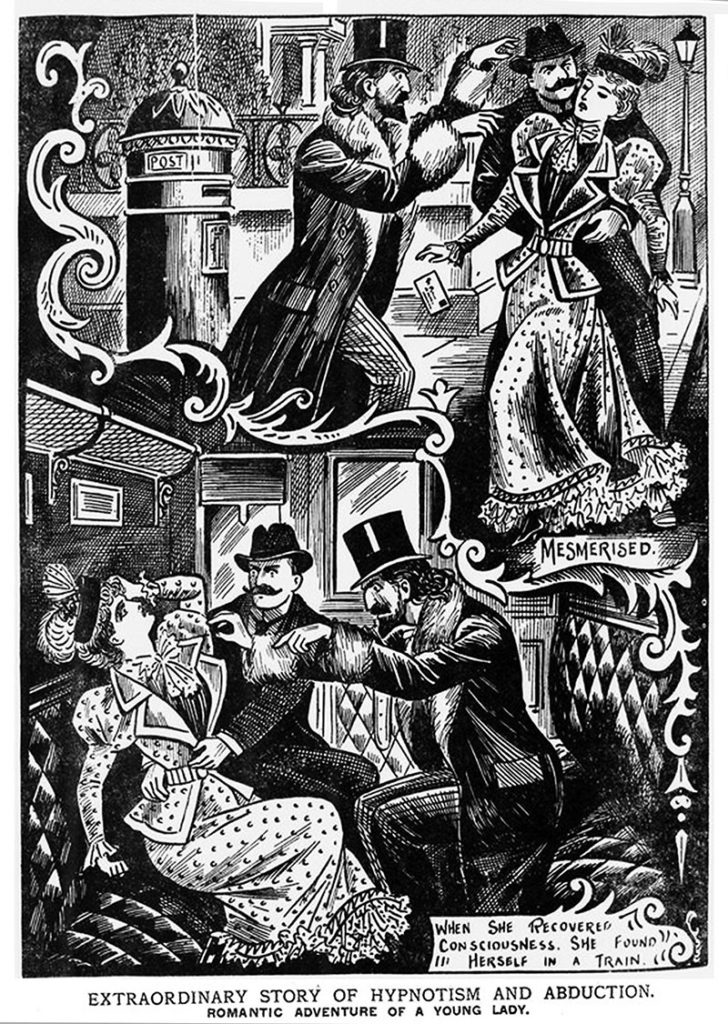

Hypnosis and abduction. Image courtesy of Donald Hartman.

A similar case happened in New Jersey in 1909 when hypnotist Arthur Everton brought Robert Simpson to the stage. The volunteer never awoke from his trance. Read more about that case in this earlier Weird Historian story.

A new book edited by Donald Hartman, Death by Suggestion: An Anthology of 19th and Early 20th-Century Tales of Hypnotically Induced Murder, Suicide and Accidental Death (Themes & Settings in Fiction), offers more than twenty short stories of hypnotism mishaps in Victorian and Edwardian fiction.

For example, in the 1896 tale, A Hypnotic Crime, by Willard Douglas Coxey, a man is put under a trance and delights the crowd by acting out an imaginary murder. The next morning his wife is found dead, lying next to him in bed. He’s arrested but maintains his innocence until the events of the previous evening come back to him: “Now it all passes before me like a panorama—the séance—the hypnotic trance—the—murder! Do with me as you will—for I killed her—I killed her—I killed my wife!”

Hartman has spent more than thirty years collecting references to hypnotism in nineteenth- and early twentieth-century writings “plowing through old magazines, books, and databases.” The recently retired reference librarian got interested in the topic early in his career while creating book displays.

“One of my colleagues suggested the topic of hypnotism to me, and I personally have a strong interest in themes and settings in fiction, so I focused my first book display on the topic of hypnotism and its portrayal in works of fiction,” Hartman said.

Since then he has amassed more than 800 related works. Clearly there was a strong fascination with the subject at the turn of the century. So what made it so popular?

Death by Suggestion, by Donald Hartman, features more than twenty short stories about hypnosis gone wrong.

“One reason was medical,” Hartman explained, “before the invention of painkillers and chloroform medical hypnotism/mesmerism was one means to deaden pain during surgery and dental extraction.”

The bigger reason, however, may be much more psychological.

Hartman referenced a book called Overpowered! The Science and Showbiz of Hypnosis, by Christopher Green, which he believes “provides the main reason why the Victorians were captivated by hypnotism, and the reason we moderns are still enthralled by it.”

In the book, Green states that “being conscious may be beneficial, but it’s also hard work. Relentless. And so much of our culture seems to be about relinquishing this responsibility for ourselves. We like being overpowered, although we know we shouldn’t. It’s no wonder, then, that hypnosis fascinates us—though with a dose of fear and a dash of mockery to guard against it. … Ultimately, hypnosis encourages all of us to examine our relationship with our own consciousness. This is less diverting, and much more hard work, but in the long run much more profound, than men in cheap suits getting people to pretend to be chickens. At its best, hypnosis demands that we look at the story we tell ourselves about ourselves. It shines a light on that self-narrative, and firmly yet gently encourages us to retell this story. And the possibilities arising from that are endless.”

As long as those possibilities don’t include murder—accidental or otherwise.