Edison’s Talking Doll, as seen at the Thomas Edison National Historical Park. This one sings Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star. Photo by Marc Hartzman.

One hundred years before Teddy Ruxpin was chatting it up with adoring kids, Thomas Edison introduced the first talking doll. But instead of designing it to be cute and cuddly, it was creepy and shoddy.

The dolls weighed around four pounds, had porcelain heads and wooden limbs. Inside the torso was a variation of the inventor’s recent phonograph technology. In 1877, Edison had reproduced sound for the first time with the invention. Now, he looked to extend it into a toy. It seemed like a great idea—just turn the crank and nursery rhymes or other recordings would play.

The June 4, 1888 edition of The Daily Argus described a small, round object as “Edison’s latest electrical ‘fad,’ so to speak. It is a small phonograph to be placed inside of a doll. The machine is placed in a tin case, and the case is put inside of the doll. By turning a small crank the doll will say: ‘Mamma, I love you.’ or anything that the inventor chooses to speak into it when it is made. Not only will the toy be very profitable, but it will add another laurel to the brow of the ingenious inventor.”

Edison employed a team of women to make the recordings (thankfully it was one task he did not take on himself).

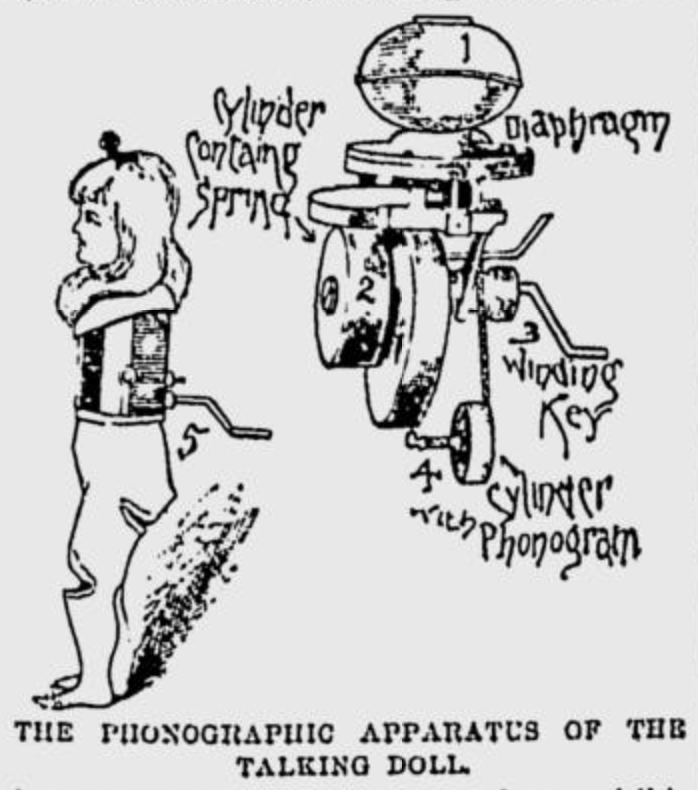

Edison’s talking doll, illustrated in The Sidney Journal, Sept. 19, 1890. Fig. 1 is the diaphragm. Fig. 2 is the cylinder containing the spring. Fig. 3 is the winding key. Fig. 4 is the cylinder with phonogram. Fig. 5 is the doll with the apparatus adjusted.

Unfortunately, sturdy as the wooden limbs were, the mechanics didn’t stand a chance against excited kids. The crank fell off easily and the phonograph was fragile. The Thomas Edison National Historical Park reports that in 1889, a seller wrote Edison complaining that “the solid wax Phonograms” used in his sample dolls were “very fragile and are, I find easily broken in changing to and from the Phono.” He added, “I am confident that the more delicate parts now contained in the Phono. must be removed and more substantial parts substituted, particularly for use in dolls, as they will be handled mostly by children, who are not as a rule very careful.”

This was just one of many gripes about the doll’s construction. By October of 1890 Edison’s doll had fallen $50,000 in debt. The company could no longer afford to manufacture more of the toys or attempt to improve them.

The Daily Argus, reporting once again on the doll in February of 1891, changed its tune on the invention: “The failure of the experiment will inspire very little regret in the hearts of fathers and mothers. It will be a good deal of money in the pockets of Santa Claus. Moreover, any little girl ought to be satisfied with a doll that has real hair and that can wake up and go to sleep. Dolls that can whistle, cry and sing ‘Annie Rooney’ can be dispensed with for the present.”

Dolls have come along way since, but for those wanting one that sings “Annie Rooney,” the wait continues.

Play the video below to hear the doll pictured above sing Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star (best not to do it before going to bed).

Enough of talking dolls? Read about Edison’s attempt to capture talking ghosts.