The year was 858 and the faithful were abuzz as the Easter Day Procession wound its way through the crowded streets of a medieval Rome. Amid the pomp and circumstance, wide-eyed worshipers along the parade route jockeyed for position — all to bear witness to an astonishing sight rivaling anything in the scriptures — His Holiness, Pope John VIII, giving birth in the middle of the papal march. Or so the story goes.

The legend of Pope Joan, as she was to become known, was first chronicled by a Dominican friar named Jean de Mailly in the late 13th century:

Concerning a certain Pope or rather female Pope, who is not set down in the list of Pope or Bishops of Rome, because she was a woman who disguised herself as a man and became, by her character and talents, a curial secretary, then a Cardinal and finally Pope. — Chronica Universalis Mettensis

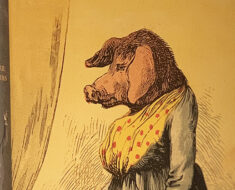

Illustrated manuscript depicting Pope Joan with the papal crown. Bibliothéque national de France, circa 1560. Artist unknown. Public domain.

Widely believed for centuries after Mailly’s original writings, the story of Pope Joan was propagated and expanded upon by later authors and artists; going so far as to even give a name to this mysterious figure:

John Anglicus, born at Mainz, was Pope for two years, seven months and four days, and died in Rome, after which there was a vacancy in the Papacy of one month. It is claimed that this John was a woman, who as a girl had been led to Athens dressed in the clothes of a man by a certain lover of hers. There she became proficient in a diversity of branches of knowledge, until she had no equal, and, afterward in Rome, she taught the liberal arts and had great masters among her students and audience. A high opinion of her life and learning arose in the city; and she was chosen for Pope.

— Martin of Opava, Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum

While subsequent versions over the centuries have differed in areas detailing the infamous event, the single commonality recounts a fascinating tale of a scholarly woman, who upon disguising herself as a man, rose through the Church hierarchy to be elected Pope John VIII.

As to what happened immediately following this supposed Easter Day “surprise” is up to debate. While some accounts describe the Popess and her child as having been merely exiled to a distant Vatican estate, Jean de Mailly’s original recount describes a much less benign ending:

“One day, while mounting a horse, she gave birth to a child. Immediately, by Roman justice she was bound by the feet to a horse’s tail and dragged and stoned by the people for half a league, and, where she died, there she was buried.”

In the Chronicon Pontificum et Imperatorum, Martin of Opava goes on further to describe the lingering effects of this supposed incident by remarking that “while Pope, however, she became pregnant by her companion. Through ignorance of the exact time when the birth was expected, she was delivered of a child while in procession from St. Peter’s to the Lateran, in a lane once named Via Sacra (the sacred way) but now known as the ‘shunned street.’ The Lord Pope always turns aside from the street, and it is believed by many that this is done because of abhorrence of the event. Nor is she placed on the list of the Holy Pontiffs, both because of her female sex and on account of the foulness of the matter.”

Though fantastical as this story may sound, not only was it common in medieval Europe for women to masquerade as men, but the over-sized, holy vestments could make it easy for a woman to hide her gender, and even a pregnancy.

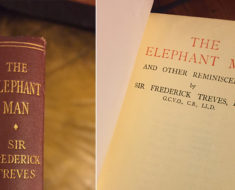

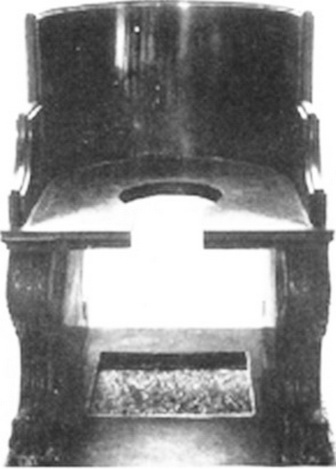

The sedia stercoraria.

While official Vatican records make no mention of the existence of a female pope, and most modern day scholars dismiss the accounts as mere myth or early anti-papal satire, there exists a curious oddity within the present day, Vatican Museum.

Known as the “dung or pierced chair,” historians and Vatican officials alike claim that the sedia stercorario is nothing more than a Papal commode or imperial birthing chair. Yet, for centuries after this alleged tale took place, it was widely reported that this object served a more pointed purpose.

According to these accounts, upon the eve of election, Popes were required to fully disrobe and sit — allowing the entire College of Cardinals to file past and verify the Pope-elect’s male gender. If such a ritual did actually take place than it would no doubt serve to finally answer an age-old question: “how’s it hanging?”